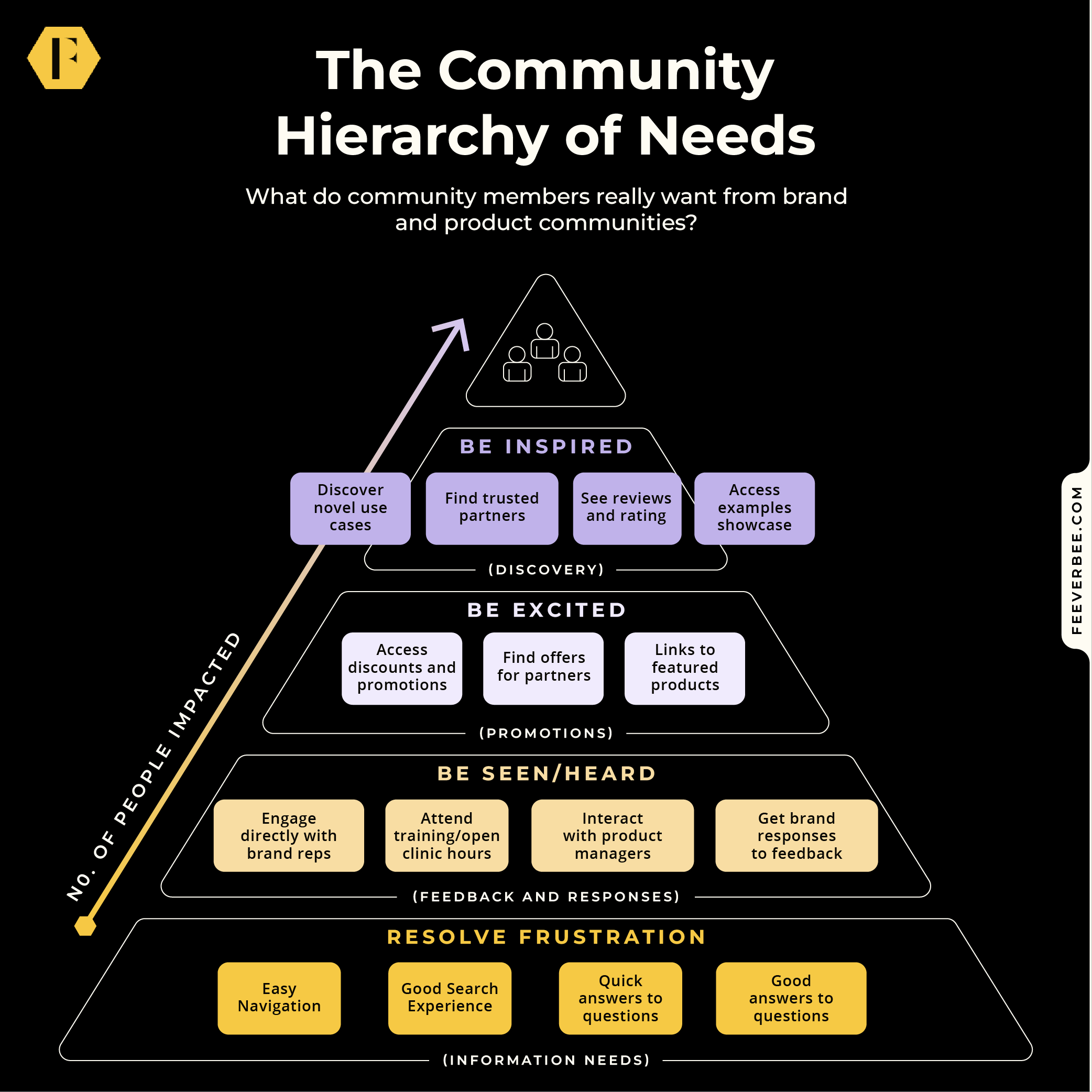

There is a common mistake in community strategies which does enormous long-term harm.

The mistake is fighting member preferences.

When your strategy supports member preferences, you’re usually going to succeed.

When your strategy fights (or tries to change) member preferences, your odds of success plummet.

The problem is member preferences and organisation ideals often clash with each other. And when they do, it’s the preferences which need to win.

You have to adapt to member preferences, not expect member preferences to adapt to your organisation.

Let’s review a few examples of things you can improve now.

Turning Experts Into A Content-Generating Machine

The big problem with most customer success communities (or any communities predicated on experts proactively sharing expertise as opposed to responding to questions), is the location.

Organisations want experts to share knowledge on a platform they control. They want to be able to easily measure success and share the content as they like.

But it’s obvious where experts want to share advice today.

They want to share advice on YouTube, Twitter, Threads, Blogs, Instagram, and other platforms.

They want to use these platforms for three reasons. These are:

- They can build their own following.

- They can share content in aesthetically pleasing ways.

- They have the opportunity to ‘go viral’.

If you create a strategy which helps experts achieve these goals you can encourage a lot more experts to share a lot more expertise.

But to make that work you have to make a sacrifice – it won’t happen on your platform.

You need to adapt to their needs, not expect them to adapt to you.

This strategy involves highlighting top experts customers should follow and featuring them in your platform.

It might be aggregating links to their content in your community.

It might be providing experts with inside information and advice.

It might experts with advice to have their content featured in the community to a bigger audience.

If you do this you can nurture and nurture a plethora of experts – each building and supporting their own tribes.

But it won’t be on a neat, single, platform. Luckily, it doesn’t need to be.

As long as your audience is reading and learning from these experts, does it matter what platform they do it on?

Nurturing Groups Which Actually Thrive

Here’s a simple question; where do you participate in groups with others today?

I’m guessing the answer is a combination of group messaging apps (WhatsApp, Slack, Discord, Telegram etc…) and possibly one or two platform-related groups (Facebook Groups, LinkedIn groups etc…).

How often do you participate in sub-groups hosted on a central brand platform?

If you’re like most people, the answer is never.

Yet time and time again organisations try to launch sub-groups on their brand platform and quickly discover most, if not all, don’t gain any traction.

The problem is organisations encumber these groups with two insurmountable burdens.

- They force members to use forum-style group experiences. People want to chat in groups, not post forum-style discussions. They value simplicity and ease of conversation above all else. Most sub-group experiences today are sadly simply a smaller version of the larger community platform experience. That’s a problem.

- They neglect the importance of leaders. When you create a group without a passionate leader, your odds of success are incredibly slim. Groups need great leaders to thrive. Too often organisations launch groups without having someone truly committed to making it thrive.

A far better approach (and one aligned with audience preferences) is to identify and encourage leaders to build groups on any platform which suits them. They know their audience better than you. Support the people who want to lead.

If someone wants to create their own group, give them the tools, resources, and knowledge to do it. Support them to build the group on any channel and in any destination which makes sense to them

If they have an existing group (on any platform) encourage them to come to you for support. You can help promote it to segments of your customers, provide advice, and give them a degree of internal access to make it work.

You should also help your audience find groups right for them. Create a portal for your audience to browse the available groups and join the ones which are a great fit for them.

It won’t be neat and tidy within a single platform. But it will be far more successful in the long term.

The Problem With Creating A Place For People To Talk About ‘The Topic’

Another common mistake is creating a place within an existing community (or on a forum-style community) for people to talk about the topic (i.e. not ask questions and discuss the brand but to ask questions and discuss the industry).

You can find some great examples (and approaches) which work well.

However, when you want to talk about a topic, where do you go?

Use our industry of community professionals if you like.

Where do you go to talk and learn about this industry?

Do you go to a single, central, forum-style platform and only participate there?

Or do you participate in conversations across the web? Do you follow several different sources of information? Are you a participant in a smattering of private groups? Do you attend various events from various organisations? Do you comment and engage with people on social media?

Unsurprisingly this is what most people do for almost any topic.

Yet when organisations attempt to build a community about the topic, they take the complete opposite approach to member preferences.

Instead of facilitating engagement across the very channels their audience wants to use, they focus all their efforts on a (typically) doomed attempt to get people to engage on a single platform they control (often as a side effort to their current Q&A-style community).

Forums still have their place as Q&A destinations – but if you want to become the place where people ask questions about the industry you’re going to first need to be VERY sure there are a lot of people already asking a lot of questions (enough to sustain a critical mass). You also need to be equally sure you can offer them a better experience than a subreddit can.

Even then you’re likely going to be limited to the Q&A experience and still need to build a broader community via engagement in multiple channels.

Community-Maintained Wikis / Tribal Knowledge Bases

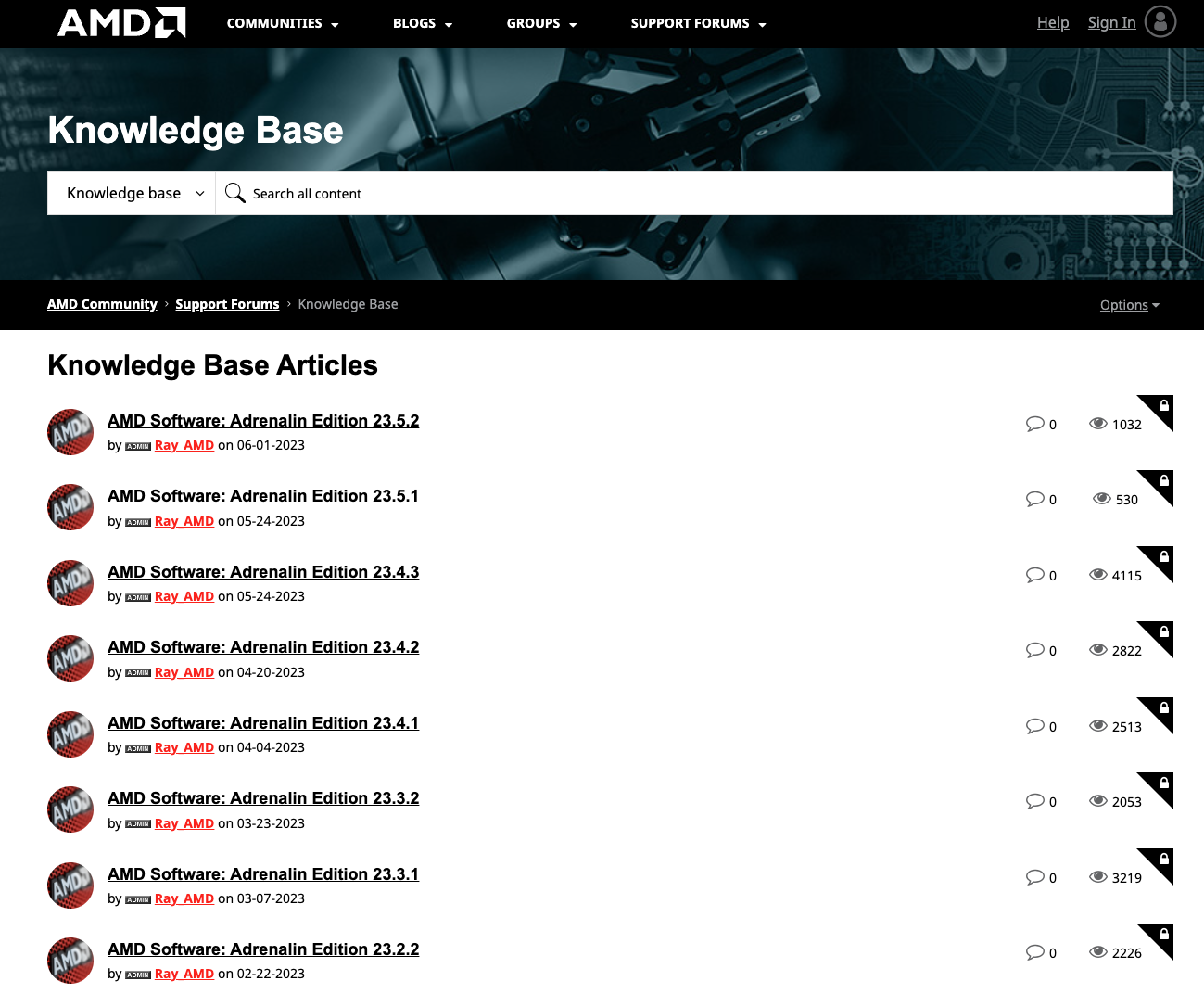

Another classic example is community-style wikis (or tribal knowledge bases).

I can’t think of a more classic example where brand expectations clash with member behaviours.

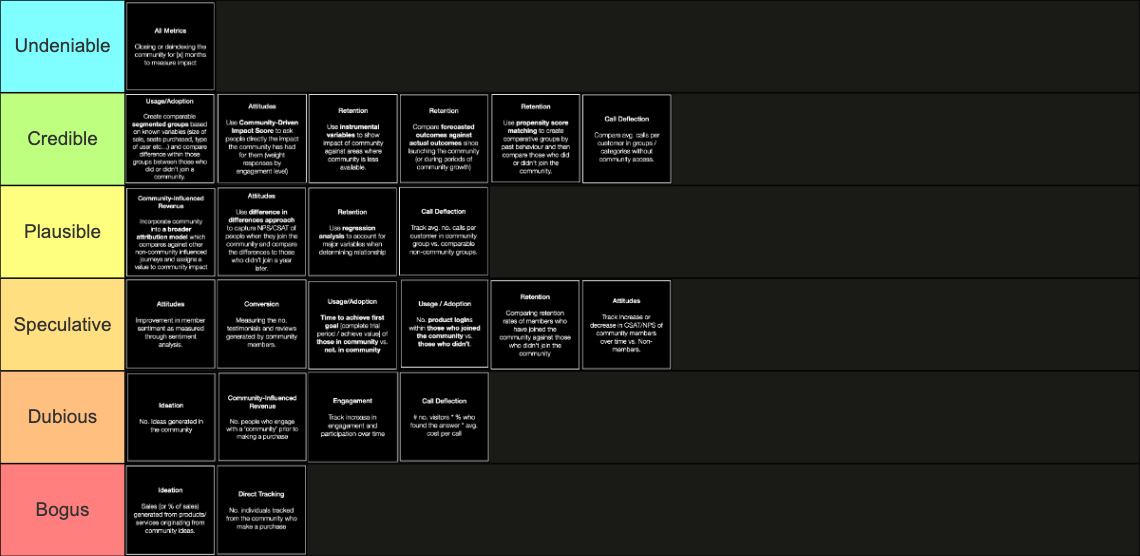

The vast majority of these types of wikis look like this:

They’re either empty or have one or two people (often brand representatives) creating all the content. This blurs the line between a knowledge base and documentation.

Perhaps the best example is Alteryx which uses the knowledge base not as a means for members to create and share articles but to share lessons hosted within the community platform itself.

It should be obvious that almost no one wants to spare time writing documentation which will be hosted in an obscure area of the community – especially when they know they can create a YouTube video sharing the same beginner-level material and attract a 100x bigger audience.

Yet too many organisations still believe this is what a significant number of members want to do. Alas, they don’t.

If you need members to create and share their own knowledge in this style format (which itself isn’t a given), then you can either get really good at converting questions to knowledge base articles (which some platforms let you do) or create the topics yourself and then find a link to and find answers across the web.

This might include embedding a YouTube video or a Twitter thread etc…Take advantage of the knowledge people are already creating out there and you are likely to encourage more of it.

Adapt To Preferences, Don’t Change Them

Trying to change the preferences of an audience is incredibly hard. You significantly reduce your odds of success if you try to persuade your audience to do what you want instead of supporting them to do what they want.

A great strategy seeks to understand preferences and then adapt to them. This isn’t easy. It typically means having less control, but more success. It makes measurement and attribution painfully tricky, but not impossible.

Difficulty in measuring success is a good problem to have compared with not having success to measure. Pursuing an approach based entirely on how easy it is to measure success is a terrible idea (but surprisingly common in practice).

Whenever you have the option, always try to support members in what they want to do rather than changing what members want to do.